The Linux exec command is a bash builtin and a very interesting utility. It is not something most people who are new to Linux know. Most seasoned admins understand it but only use it occasionally. If you are a developer, programmer or DevOp engineer it is probably something you use more often. Lets take a deep dive into the builtin exec command, what it does and how to use it.

Table of Contents

Basics of the Parent / Child Process

In order to understand the exec command, you need a fundamental understanding of how shells create (fork) processes. When you open a terminal window a program is started, in my case gnome-terminal-server. That program creates a new “bash” process and gives you a command prompt. Most commands entered in the terminal window create a new child process.

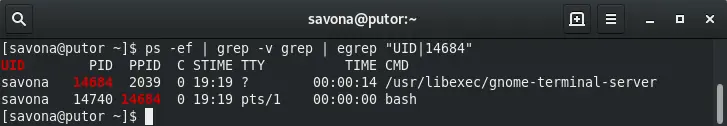

Below is an example. I opened a terminal window which started the gnome-terminal-server. The Gnome terminal process created a bash process and gave me a prompt. Below you will see the PID (Process ID) of the Gnome Terminal is 14684. If you look closely as the bash process you will see it’s PPID (Parent Process ID) is the same. This means that it is a child process of the gnome-terminal-server.

Every time you run a command in a terminal, it creates (forks) a child process and runs the supplied command.

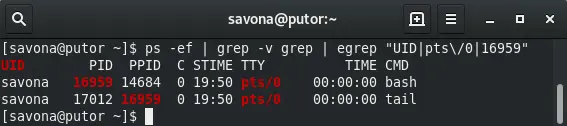

In the next example, I opened a second terminal window. I then ran the tail command. Bash creates a child process to run the tail command. We can prove this happened by once again looking at the process ID and Parent Process ID. In the screenshot below you can see the parent process for the tail command is the process ID of the original bash terminal.

That is a very basic example of how shells create child processes to execute commands. I will leave links to more information about child processes and sub-shells in the resources section at the end of this article. Now, on to the main event, the exec command.

What the Exec Command Does

In it’s most basic function the exec command changes the default behavior of creating a sub-shell to run a command. If you run exec followed by a command, that command will REPLACE the original process, it will NOT create a sub-shell.

An additional feature of the exec command, is redirection and manipulation of file descriptors. Explaining redirection and file descriptors is outside the scope of this tutorial. If these are new to you please read “Linux IO, Standard Streams and Redirection” to get acquainted with these terms and functions.

In the following sections we will expand on both of these functions and try to demonstrate how to use them.

How to Use the Exec Command with Examples

Let’s look at some examples of how to use the exec command and it’s options.

Basic Exec Command Usage – Replacement of Process

If you call exec and supply a command without any options, it simply replaces the shell with command.

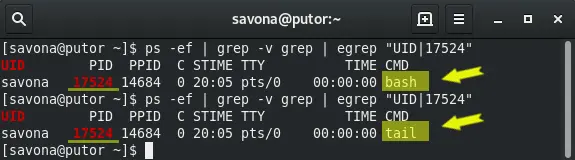

Let’s run an experiment. First, I ran the ps command to find the process id of my second terminal window. In this case it was 17524. I then ran “exec tail” in that second terminal and checked the ps command again. If you look at the screenshot below, you will see the tail process replaced the bash process (same process ID).

Since the tail command replaced the bash shell process, the shell will close when the tail command terminates.

Exec Command Options

If the -l option is supplied, exec adds a dash at the beginning of the first (zeroth) argument given. So if we ran the following command:

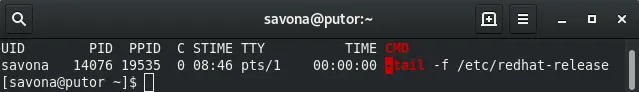

exec -l tail -f /etc/redhat-release

It would produce the following output in the process list. Notice the highlighted dash in the CMD column.

The -c option causes the supplied command to run with a empty environment. Environmental variables like PATH, are cleared before the command it run. Let’s try an experiment. We know that the printenv command prints all the settings for a users environment. So here we will open a new bash process, run the printenv command to show we have some variables set. We will then run printenv again but this time with the exec -c option.

In the example above you can see that an empty environment is used when using exec with the -c option. This is why there was no output to the printenv command when ran with exec.

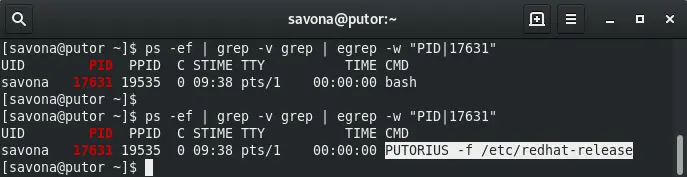

The last option, -a [name], will pass name as the first argument to command. The command will still run as expected, but the name of the process will change. In this next example we opened a second terminal and ran the following command:

exec -a PUTORIUS tail -f /etc/redhat-release

Here is the process list showing the results of the above command:

As you can see, exec passed PUTORIUS as first argument to command, therefore it shows in the process list with that name.

Using the Exec Command for Redirection & File Descriptor Manipulation

The exec command is often used for redirection. When a file descriptor is redirected with exec it affects the current shell. It will exist for the life of the shell or until it is explicitly stopped.

If no command is specified, redirections may be used to affect the current shell environment.

– Bash Manual

Here are some examples of how to use exec for redirection and manipulating file descriptors. As we stated above, a deep dive into redirection and file descriptors is outside the scope of this tutorial. Please read “Linux IO, Standard Streams and Redirection” for a good primer and see the resources section for more information.

Redirect all standard output (STDOUT) to a file:

exec >file

In the example animation below, we use exec to redirect all standard output to a file. We then enter some commands that should generate some output. We then use exec to redirect STDOUT to the /dev/tty to restore standard output to the terminal. This effectively stops the redirection. Using the cat command we can see that the file contains all the redirected output.

Open a file as file descriptor 6 for writing:

exec 6> file2write

Open file as file descriptor 8 for reading:

exec 8< file2read

Copy file descriptor 5 to file descriptor 7:

exec 7<&5

Close file descriptor 8:

exec 8<&-

Conclusion

In this article we covered the basics of the exec command. We discussed how to use it for process replacement, redirection and file descriptor manipulation.

In the past I have seen exec used in some interesting ways. It is often used as a wrapper script for starting other binaries. Using process replacement you can call a binary and when it takes over there is no trace of the original wrapper script in the process table or memory. I have also seen many System Administrators use exec when transferring work from one script to another. If you call a script inside of another script the original process stays open as a parent. You can use exec to replace that original script.

I am sure there are people out there using exec in some interesting ways. I would love to hear your experiences with exec. Please feel free to leave a comment below with anything on your mind.

Resources

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

1 Comment

Join Our Newsletter

Categories

- Bash Scripting (17)

- Basic Commands (51)

- Featured (7)

- Just for Fun (5)

- Linux Quick Tips (98)

- Linux Tutorials (65)

- Miscellaneous (15)

- Network Tools (6)

- Reviews (2)

- Security (32)

- Smart Home (1)

I think a subshell is an instance of the shell (https://www.tldp.org/LDP/abs/html/subshells.html).

In your case tail is not executed by a subshell, it’s a process executed by the shell. On the other hand, if you want to execute a shell script, then the shell will create a subshell which in turn will execute the script.

Also, the very first statement of the article “The Linux exec command is a bash builtin” is not 100% correct. The word “Linux” is misleading and not needed 🙂